Event Recap

Data & Society, an independent, nonprofit research institute in NYC whose mission is to “advance public understanding of the social implications of data-centric technologies and automation,” hosted their first collective reading on the Feminist Data Manifest-No on February 5th. The Feminist Data Manifest-No, in laying a groundwork for ethical research practices, seemed like a worthy addition to the PSMF’s Critical Scholarly Communication project’s online research guide, which seeks to compile and disseminate digital scholarly communication from a critical perspective, so I attended the event and wrote up a brief recap below.

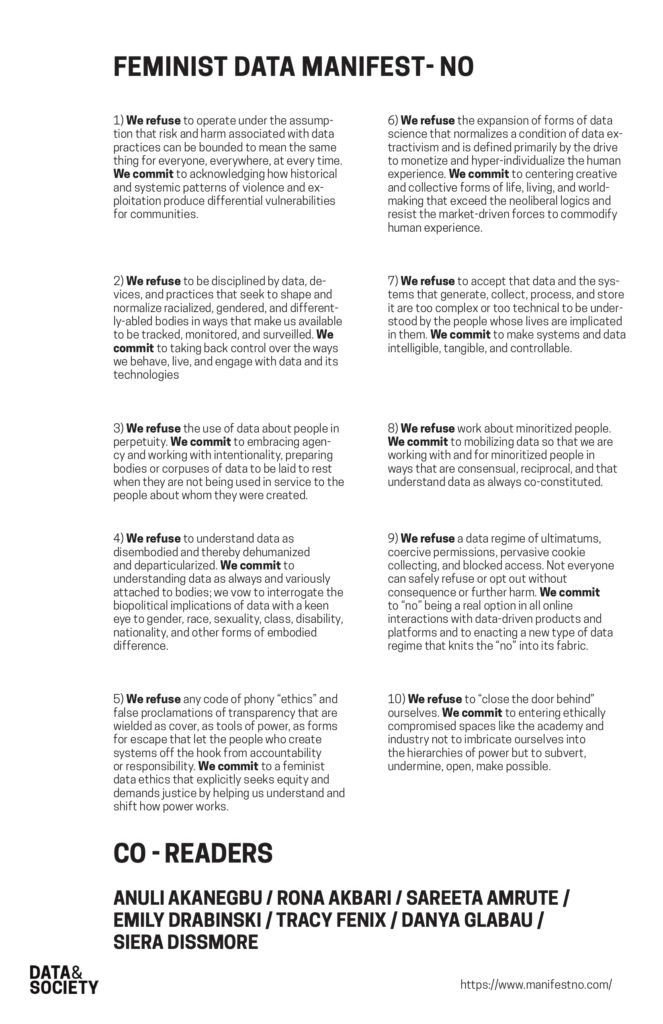

The gathering felt casual and comfortable, with people lounging on sofas and chairs (see image above), rather than sitting upright in rows of plastic chairs. The event was organized into three straight-forward parts: an introduction, public reading of ten declarations from the Feminist Data Manifest-No, and Q&A Session.

I. Introduction

Presenters Marika Cifor (University of Washington – Seattle), Patricia Garcia (University of Michigan – Ann Arbor), and Anita Say Chan (Data & Society) introduced the Feminist Data Manifest-No, a product of a collaborative brainstorming session during a “Feminist Data Studies Workshop” in August 2019, which brought together ten feminist scholars across various disciplines. These co-authors include Marika Cifor, Patricia Garcia, Anita Say, TL Cowan, Jasmine Rault, Tonia Sutherland, Jennifer Rode, Anna Lauren Hoffman, Nilofar Salehi, and Lisa Nakamura.

The manifesto has at its core the centralizing theme of the “Act of Refusal,” which embodies feminist history and struggles, and presents over thirty declarations which seek to promote and create fair, equal, and safe data practices for everyone. The creators of the Feminist Data Manifest-No further define their mission on their website:

“Our refusals and commitments together demand that data be acknowledged as at once an interpretation and in need of interpretation. Data can be a check-in, a story, an experience or set of experiences, and a resource to begin and continue dialogue. It can – and should always – resist reduction. Data is a thing, a process, and a relationship we make and put to use. We can make it and use it differently.”

–https://www.manifestno.com/

The Feminist Data Manifest-No is licensed through Creative Commons, a platform which the organizers feel will encourage the document to be a living product and which will engender additional contributions from others.

II. Public Reading of the Feminist Data Manifest-No

Ten declarations from the Feminist Data Manifest-No, which had been handed out to attendees before the event started, were read out loud by the three presenters, as well as by Anuli Akanegbu (PhD student in NYU’s Sociocultural Anthropology Department), Rona Akbari (writer and producer), Sareeta Amrute (Director of Research at Data & Society), Siera Dissmore (Program Manager of Reserach at Data & Society), Emily Drabinski (Associate Professor and Critical Pedagogy Librarian at The Gradaute Center, CUNY), Tracy Fenix (Artist+ Registry & Archive Associate at Visual AIDS), and Danya Glabau (Visiting Industry Assistant Professor and Interim Director of the Science and Technology Studies program at the NYU Department of Technology).

III. Q&A Session

The Question-and-Answer section made up the majority of the event, which is perhaps reflective of the Feminist Data Manifest-No’s mission to include and integrate the public, creating a set of ethical practices both by and for the people.

Below, I have paraphrased some of the questions and comments posed by the audience in response to the reading of the ten above declarations:

- Question: Some of the language used in the Feminist Data Manifest-No, such as “imbricate” seems inaccessible to the public–if the goal of these declarations is in part to support those who are underrepresented or oppressed, then shouldn’t a more simple vocabulary be employed?

Answer: We feel that we should not be making generalizations about the education level of the “general public”; the document should serve as a provocation, imploring one to ask of oneself, “What does this manifesto mean for me?” - Comment: In the wake of all the technological advances in our era, it is easy to ignore the reach of one’s own voice and difficult to control its potential amplification. We need to be centering this Feminist Data Manifest-No around our rights as a tangible, human body.

- Comment: Venture capitalists would not be interested in projects like this, and therefore it would be difficult to achieve the proper funding and reach.

- Question: Is the title “Feminist Data Manifesto-No” a little restrictive? Specifically, does the word “feminist” alienate others?

- Comment: As a lawyer, I am shocked by the amount of private data we collect and hold onto in perpetuity. I have witnessed that this data only serves to harm the clients it is meant to protect. We should support movements like “Ban The Box.”

- Question: Should we be concerned with the collection and saving of data that isn’t ours?

Overall, the event served to raise more questions than it answered, but it was nevertheless an important–and necessary–conversation starter. How these declarations will be translated into action remains unclear at this point in time, but it is ultimately the responsibility of the people who share and contribute to the Feminist Data Manifest-No to create tangible changes in data practices. We hope that by spreading awareness of this resource on Social Mediums, the manifesto will receive a stronger voice.